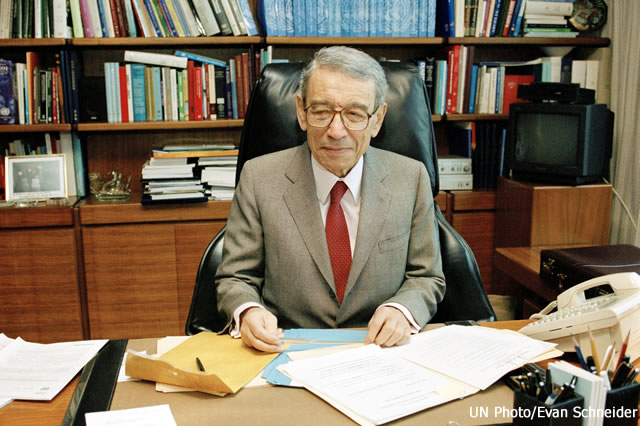

Boutros Boutros-Ghali: A personal tribute

This article was originally published by Al-Ahram Weekly

Boutros Boutros-Ghali believed in parliamentarians, and they believed in him, writes Shazia Rafi

Two days after my appointment as the first woman secretary-general of a global parliamentary body, I was still sitting in a stunned state at my desk. The intercom beeped and in a daze I heard “It’s the secretary-general’s office on line one.” In my head I thought, “You mean the real secretary-general of the United Nations?”

It was my friend Mourad Wahba, from the secretary-general’s office, calling to say, “The secretary-general is ready to give you a courtesy meeting, but you have to write formally to ask for one.” He then guided me on the protocol. Days later I was ushered in to meet His Excellency Boutros Boutros-Ghali. As his eyes widened in surprise and a smile tweaked his mouth, he came forward to put me at ease. “Madam secretary-general, congratulations!”

We sat down, with me doing a silent prayer. He watched me take a deep breath and said, “What can I do to help you?” I began my prepared pleasantries but broke with them to ask him to open my first annual forum and special parliamentary session on Africa, which was to be a parallel effort to his Special Initiative on Africa. He asked detailed questions and then asked his staff to check his December calendar, and right there we set the dates.

The meeting was over but he saw the shadow of worry on my face and gently probed, “Is there anything else you need?” I blurted, “Mr Secretary-General, I need funds to hold the forum. PGA [Parliamentarians for Global Action] has no funds.” He immediately had his staff put in a call to Mrs Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who was then the UNDP’s Africa division head, and told her he was sending me to see her. He then patted me on the back and said, “Go make a strong case and I will see you in December.”

In the days when NGOs were allowed everywhere in the UN to lobby governments, Boutros-Ghali walked the corridors with us, talked to us, spoke at our meetings, and joined substantive sessions to debate ideas. Introduced to our organisation by then convenor, Professor Mona Makram Ebeid, the secretary-general used the ideas we put forward for collective security in his Agenda for Peace.

As a former politician, Boutros-Ghali took every opportunity to interact with parliamentarians. Normal protocol would be waived aside as he responded to their invitations and plunged in to attend their national sessions. Taking time from his official 1994 visit to Delhi, he attended an informal session hosted by the chair of the India national parliamentary group, the Honourable Murli Deora, and urged parliamentarians to press their government to support UN collective security and regional peace mechanisms.

In the shadow of war and impending genocide, he engaged in substantive sessions on the Yugoslav tribunal and International Criminal Court in March 1993 with a delegation of Global Action members led by the Honourable Arthur Robinson, former prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, and Egyptian-American legal scholar Professor Cherif Bassiouni.

But the issue that most animated him was conflict prevention. In a 1994 parliamentary meeting in The Hague for creation of an early warning mechanism utilising Global Action’s established global network, calling it “an excellent idea”, adding that the action undertaken by MPs in order to draw attention to an impending crisis would strengthen his hand, under Article 99 of the UN Charter, so that he could bring such situations to the attention of the Security Council. Ironically, his will and ability to do so were soon to be put to the test in Central Africa.

Much has been written by others on the dark period of the UN’s failures in peace-keeping during the genocide in Rwanda in April 1994. I experienced firsthand how difficult it was to bring early warnings to the 38th floor. Since the October 1993 elections, I had been following the situation in neighbouring Burundi, a mirror twin to Rwanda. The signs of similar ethnic hatred, spillover violence bordering on genocide, were also evident there.

Members of parliament from Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda had been warning for months about the impending violence. The late Alison des Forges, an analyst on Rwanda/Burundi with Human Rights Watch, urged us to continue working with Burundi’s newly elected legislature and pushing the UN to prevent a similar fault line engulfing the country in genocide.

We knocked on every door in the UN, including senior officials on the 38th floor. Access to the secretary-general was blocked — it was not clear why. While I do not know when the secretary-general received notification about the start of the Rwandan genocide, I do know that he was a man committed to preventive action for peace.

A year later, while dejected by the failure of his organisation in Rwanda, addressing a session launching our Early Warning System for Conflict Prevention at the Social Summit in Copenhagen in 1995, Boutros-Ghali told legislators not to give up as they were his “eyes, ears and hearts on the ground”.

Mr Secretary-General, we have not given up.